-

How to Analyse Chemical Composition?

-

Primary and Secondary Metabolites

-

Biomacromolecules

-

Proteins

-

Polysaccharides

-

Nucleic Acids

-

Structure of Proteins

-

Nature of Bond Linking Monomers in a Polymer

-

Dynamic State of Body Constituents – Concept of Metabolism

-

Metabolic Basis for Living

-

The Living State

-

Enzymes

Chapter 9

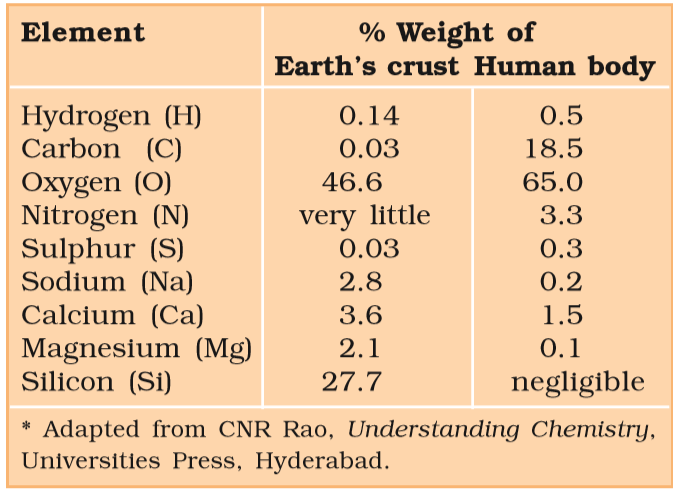

Biomolecules

There is a wide diversity in living organisms in our biosphere. Now a question that arises in our minds is: Are all living organisms made of the same chemicals, i.e., elements and compounds? You have learnt in chemistry how elemental analysis is performed. If we perform such an analysis on a plant tissue, animal tissue or a microbial paste, we obtain a list of elements like carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and several others and their respective content per unit mass of a living tissue. If the same analysis is performed on a piece of earth’s crust as an example of non-living matter, we obtain a similar list. What are the differences between the two lists? In absolute terms, no such differences could be made out. All the elements present in a sample of earth’s crust are also present in a sample of living tissue. However, a closer examination reveals that the relative abundance of carbon and hydrogen with respect to other elements is higher in any living organism than in earth’s crust (Table 9.1).

9.1 How to Analyse Chemical Composition?

9.2 Primary and Secondary Metabolites

9.3 Biomacromolecules

9.4 Proteins

9.5 Polysaccharides

9.6 Nucleic Acids

9.7 Structure of Proteins

9.8 Nature of Bond Linking Monomers in a Polymer

9.9 Dynamic State of Body Constituents – Concept of Metabolism

9.10 Metabolic Basis for Living

9.11 The Living State

9.12 Enzymes

9.1 How to Analyse Chemical Composition?

We can continue asking in the same way, what type of organic compounds are found in living organisms? How does one go about finding the answer? To get an answer, one has to perform a chemical analysis. We can take any living tissue (a vegetable or a piece of liver, etc.) and grind it in trichloroacetic acid (Cl3CCOOH) using a mortar and a pestle. We obtain a thick slurry. If we were to strain this through a cheesecloth or cotton we would obtain two fractions. One is called the filtrate or more technically, the acid-soluble pool, and the second, the retentate or the acid-insoluble fraction. Scientists have found thousands of organic compounds in the acid-soluble pool.

TABLE 9.1 A Comparison of Elements Present in Non-living and Living Matter*

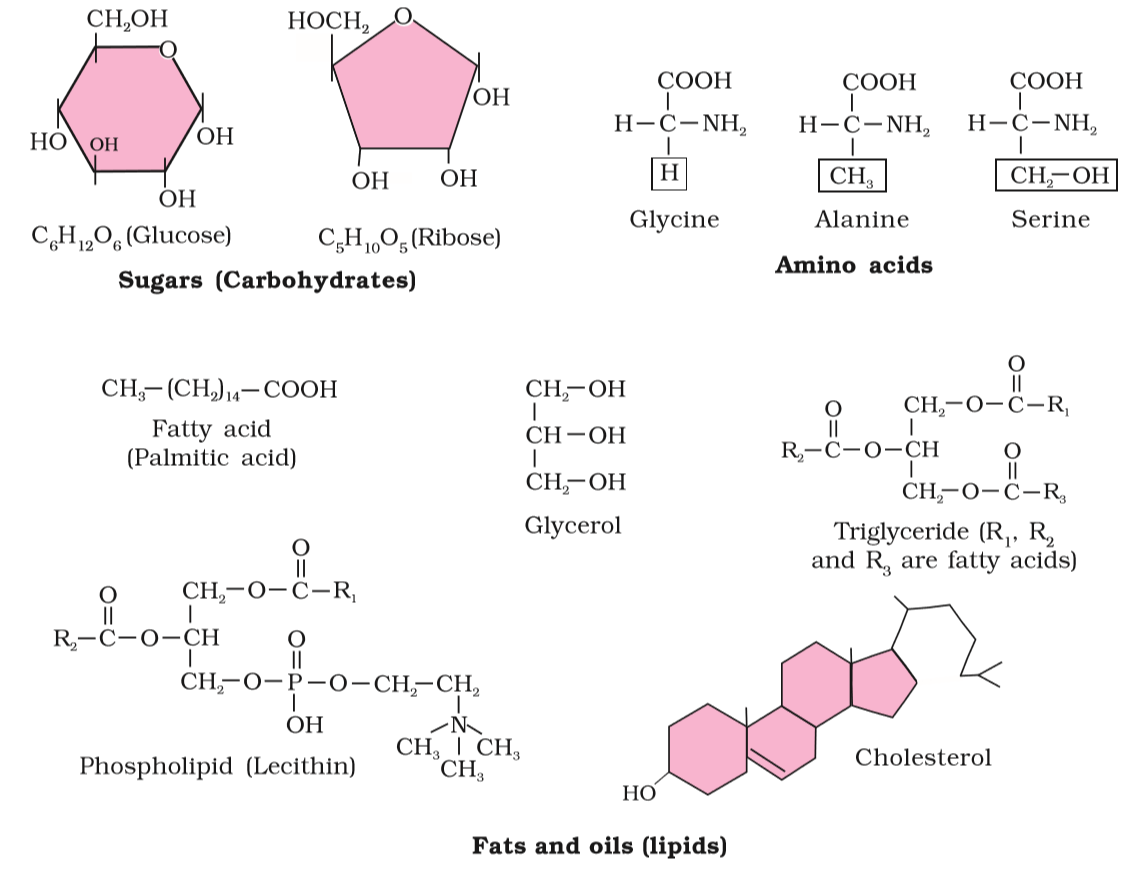

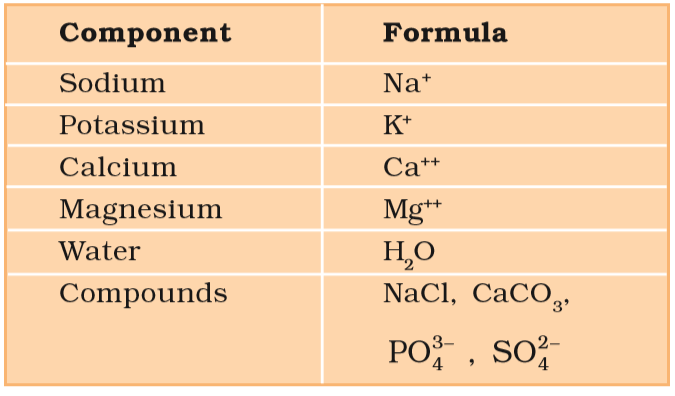

In higher classes you will learn about how to analyse a living tissue sample and identify a particular organic compound. It will suffice to say here that one extracts the compounds, then subjects the extract to various separation techniques till one has separated a compound from all other compounds. In other words, one isolates and purifies a compound. Analytical techniques, when applied to the compound give us an idea of the molecular formula and the probable structure of the compound. All the carbon compounds that we get from living tissues can be called ‘biomolecules’. However, living organisms have also got inorganic elements and compounds in them. How do we know this? A slightly different but destructive experiment has to be done. One weighs a small amount of a living tissue (say a leaf or liver and this is called wet weight) and dry it. All the water, evaporates. The remaining material gives dry weight. Now if the tissue is fully burnt, all the carbon compounds are oxidised to gaseous form (CO2, water vapour) and are removed. What is remaining is called ‘ash’. This ash contains inorganic elements (like calcium, magnesium etc). Inorganic compounds like sulphate, phosphate, etc., are also seen in the acid-soluble fraction. Therefore elemental analysis gives elemental composition of living tissues in the form of hydrogen, oxygen, chlorine, carbon etc. while analysis for compounds gives an idea of the kind of organic (Figure 9.1) and inorganic constituents (Table 9.2) present in living tissues. From a chemistry point of view, one can identify functional groups like aldehydes, ketones, aromatic compounds, etc. But from a biological point of view, we shall classify them into amino acids, nucleotide bases, fatty acids etc.

Table 9.2 A List of Representative Inorganic Constituents of Living Tissues

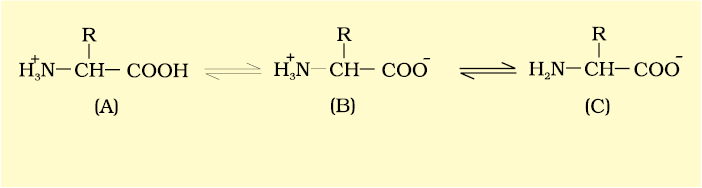

Amino acids are organic compounds containing an amino group and an acidic group as substituents on the same carbon i.e., the α-carbon. Hence, they are called α-amino acids. They are substituted methanes. There are four substituent groups occupying the four valency positions. These are hydrogen, carboxyl group, amino group and a variable group designated as R group. Based on the nature of R group there are many amino acids. However, those which occur in proteins are only of twenty types. The R group in these proteinaceous amino acids could be a hydrogen (the amino acid is called glycine), a methyl group (alanine), hydroxy methyl (serine), etc. Three of the twenty are shown in Figure 9.1.

The chemical and physical properties of amino acids are essentially of the amino, carboxyl and the R functional groups. Based on number of amino and carboxyl groups, there are acidic (e.g., glutamic acid), basic (lysine) and neutral (valine) amino acids. Similarly, there are aromatic amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan). A particular property of amino acids is the ionizable nature of –NH2 and –COOH groups. Hence in solutions of different pH, the structure of amino acids changes.

B is called zwitterionic form.

Lipids are generally water insoluble. They could be simple fatty acids. A fatty acid has a carboxyl group attached to an R group. The R group could be a methyl (–CH3), or ethyl (–C2H5) or higher number of –CH2 groups (1 carbon to 19 carbons). For example, palmitic acid has 16 carbons including carboxyl carbon. Arachidonic acid has 20 carbon atoms including the carboxyl carbon. Fatty acids could be saturated (without double bond) or unsaturated (with one or more C=C double bonds). Another simple lipid is glycerol which is trihydroxy propane. Many lipids have both glycerol and fatty acids. Here the fatty acids are found esterified with glycerol. They can be then monoglycerides, diglycerides and triglycerides. These are also called fats and oils based on melting point. Oils have lower melting point (e.g., gingelly oil) and hence remain as oil in winters. Can you identify a fat from the market? Some lipids have phosphorous and a phosphorylated organic compound in them. These are phospholipids. They are found in cell membrane. Lecithin is one example. Some tissues especially the neural tissues have lipids with more complex structures.

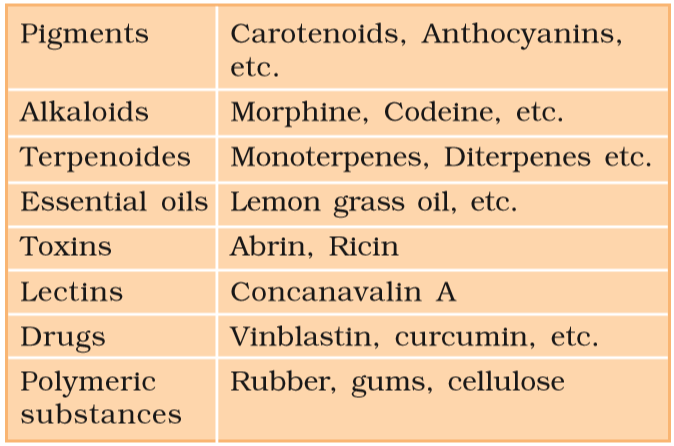

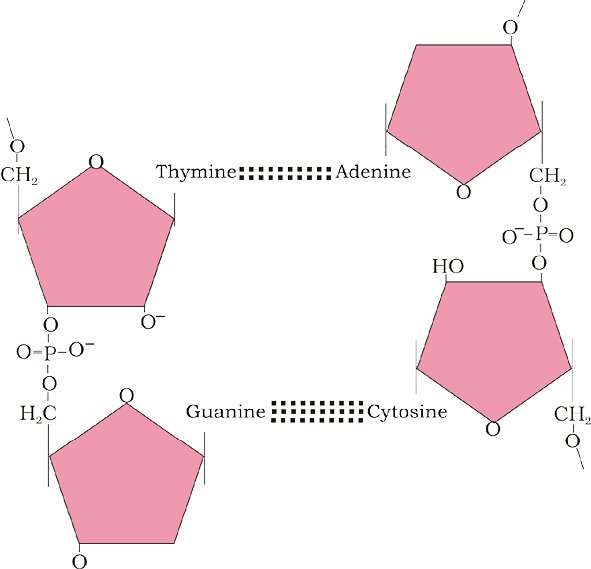

Living organisms have a number of carbon compounds in which heterocyclic rings can be found. Some of these are nitrogen bases – adenine, guanine, cytosine, uracil, and thymine. When found attached to a sugar, they are called nucleosides. If a phosphate group is also found esterified to the sugar they are called nucleotides. Adenosine, guanosine, thymidine, uridine and cytidine are nucleosides. Adenylic acid, thymidylic acid, guanylic acid, uridylic acid and cytidylic acid are nucleotides. Nucleic acids like DNA and RNA consist of nucleotides only. DNA and RNA function as genetic material.

Figure 9.1 Diagrammatic representation of small molecular weight organic compounds in living tissues

9.2 Primary and Secondary Metabolites

The most exciting aspect of chemistry deals with isolating thousands of compounds, small and big, from living organisms, determining their structure and if possible synthesising them.

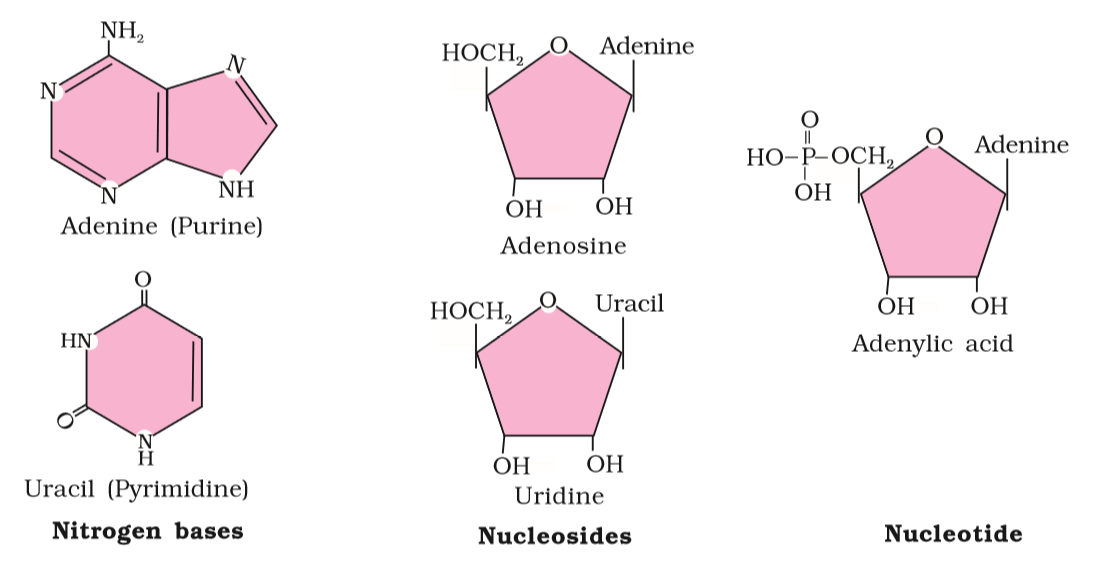

Table 9.3 Some Secondary Metabolites

9.3 Biomacromolecules

There is one feature common to all those compounds found in the acid soluble pool. They have molecular weights ranging from 18 to around 800 daltons (Da) approximately.

The acid insoluble fraction, has only four types of organic compounds i.e., proteins, nucleic acids, polysaccharides and lipids. These classes of compounds with the exception of lipids, have molecular weights in the range of ten thousand daltons and above. For this very reason, biomolecules, i.e., chemical compounds found in living organisms are of two types. One, those which have molecular weights less than one thousand dalton and are usually referred to as micromolecules or simply biomolecules while those which are found in the acid insoluble fraction are called macromolecules or biomacromolecules.

The molecules in the insoluble fraction with the exception of lipids are polymeric substances. Then why do lipids, whose molecular weights do not exceed 800 Da, come under acid insoluble fraction, i.e., macromolecular fraction? Lipids are indeed small molecular weight compounds and are present not only as such but also arranged into structures like cell membrane and other membranes. When we grind a tissue, we are disrupting the cell structure. Cell membrane and other membranes are broken into pieces, and form vesicles which are not water soluble. Therefore, these membrane fragments in the form of vesicles get separated along with the acid insoluble pool and hence in the macromolecular fraction. Lipids are not strictly macromolecules.

The acid soluble pool represents roughly the cytoplasmic composition. The macromolecules from cytoplasm and organelles become the acid insoluble fraction. Together they represent the entire chemical composition of living tissues or organisms.

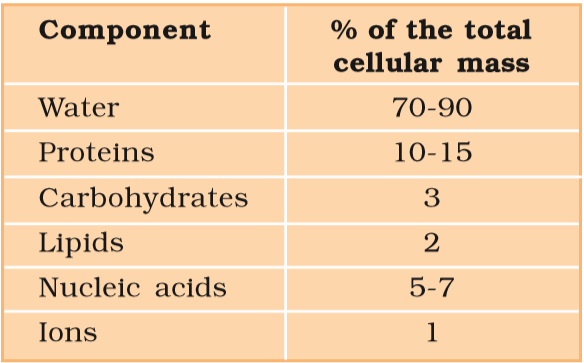

In summary if we represent the chemical composition of living tissue from abundance point of view and arrange them class-wise, we observe that water is the most abundant chemical in living organisms (Table 9.4).

9.4 Proteins

Proteins are polypeptides. They are linear chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds as shown in Figure 9.3.

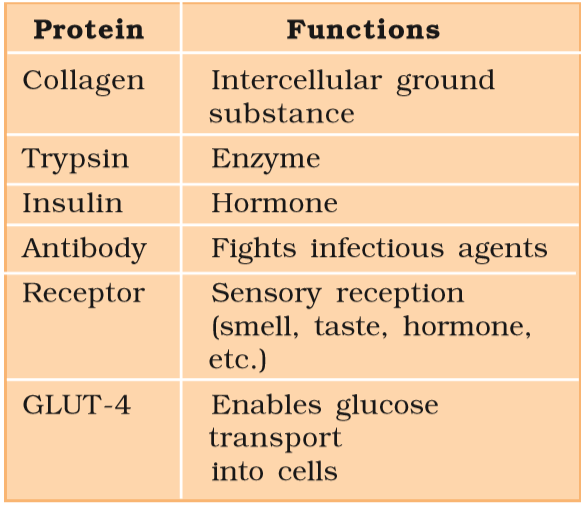

Table 9.5 Some Proteins and their Functions

Each protein is a polymer of amino acids. As there are 20 types of amino acids (e.g., alanine, cysteine, proline, tryptophan, lysine, etc.), a protein is a heteropolymer and not a homopolymer. A homopolymer has only one type of monomer repeating ‘n’ number of times. This information about the amino acid content is important as later in your nutrition lessons, you will learn that certain amino acids are essential for our health and they have to be supplied through our diet. Hence, dietary proteins are the source of essential amino acids. Therefore, amino acids can be essential or non-essential. The latter are those which our body can make, while we get essential amino acids through our diet/food. Proteins carry out many functions in living organisms, some transport nutrients across cell membrane, some fight infectious organisms, some are hormones, some are enzymes, etc. (Table 9.5). Collagen is the most abundant protein in animal world and Ribulose bisphosphate Carboxylase-Oxygenase (RuBisCO) is the most abundant protein in the whole of the biosphere.

9.5 Polysaccharides

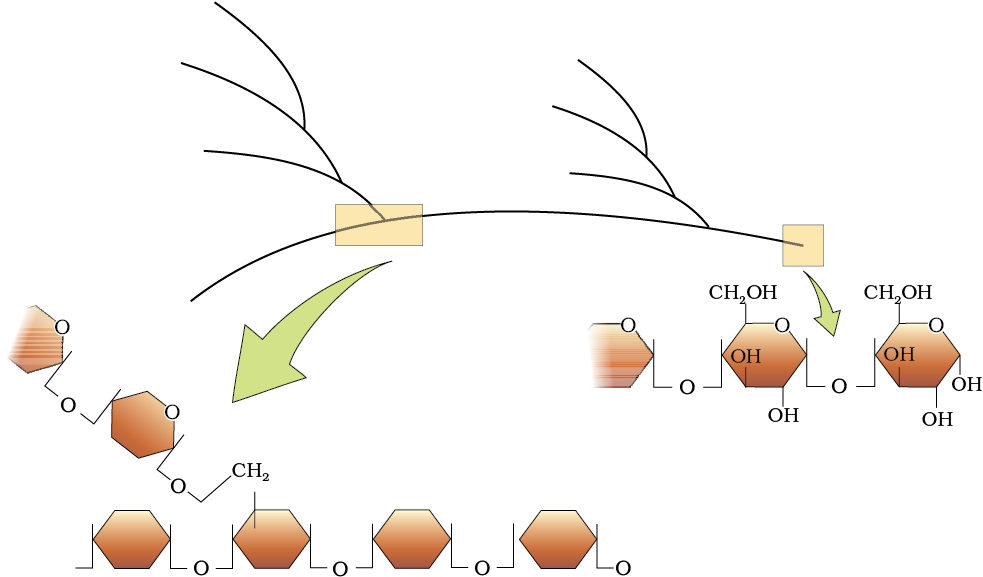

The acid insoluble pellet also has polysaccharides (carbohydrates) as another class of macromolecules. Polysaccharides are long chains of sugars. They are threads (literally a cotton thread) containing different monosaccharides as building blocks. For example, cellulose is a polymeric polysaccharide consisting of only one type of monosaccharide i.e., glucose. Cellulose is a homopolymer. Starch is a variant of this but present as a store house of energy in plant tissues. Animals have another variant called glycogen. Inulin is a polymer of fructose. In a polysaccharide chain (say glycogen), the right end is called the reducing end and the left end is called the non-reducing end. It has branches as shown in the form of a cartoon (Figure 9.2). Starch forms helical secondary structures. In fact, starch can hold I2 molecules in the helical portion. The starch-I2 is blue in colour. Cellulose does not contain complex helices and hence cannot hold I2.

Figure 9.2 Diagrammatic representation of a portion of glycogen

Plant cell walls are made of cellulose. Paper made from plant pulp and cotton fibre is cellulosic. There are more complex polysaccharides in nature. They have as building blocks, amino-sugars and chemically modified sugars (e.g., glucosamine, N-acetyl galactosamine, etc.). Exoskeletons of arthropods, for example, have a complex polysaccharide called chitin. These complex polysaccharides are mostly homopolymers.

9.6 Nucleic Acids

The other type of macromolecule that one would find in the acid insoluble fraction of any living tissue is the nucleic acid. These are polynucleotides. Together with polysaccharides and polypeptides these comprise the true macromolecular fraction of any living tissue or cell. For nucleic acids, the building block is a nucleotide. A nucleotide has three chemically distinct components. One is a heterocyclic compound, the second is a monosaccharide and the third a phosphoric acid or phosphate.

As you notice in Figure 9.1, the heterocyclic compounds in nucleic acids are the nitrogenous bases named adenine, guanine, uracil, cytosine, and thymine. Adenine and Guanine are substituted purines while the rest are substituted pyrimidines. The skeletal heterocyclic ring is called as purine and pyrimidine respectively. The sugar found in polynucleotides is either ribose (a monosaccharide pentose) or 2’ deoxyribose. A nucleic acid containing deoxyribose is called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) while that which contains ribose is called ribonucleic acid (RNA).

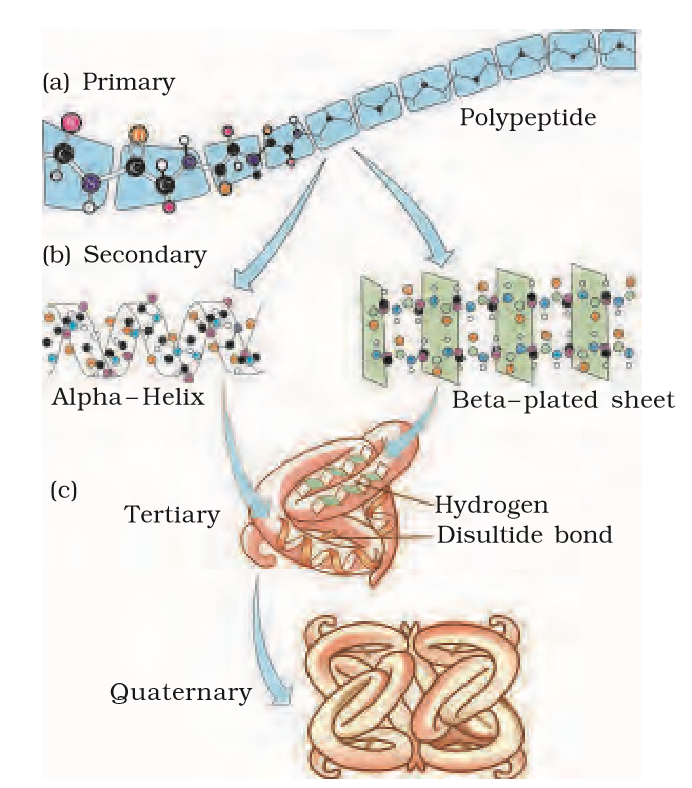

9.7 Structure of Proteins

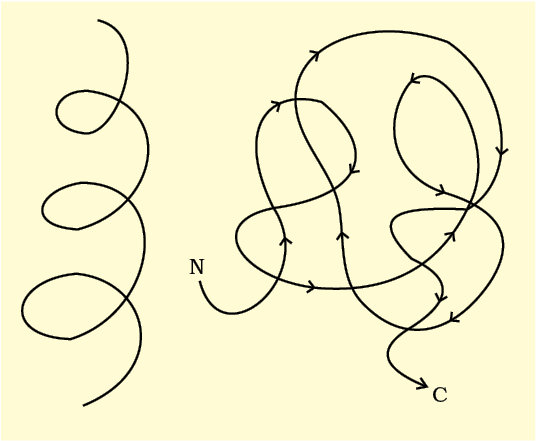

Proteins, as mentioned earlier, are heteropolymers containing strings of amino acids. Structure of molecules means different things in different contexts. In inorganic chemistry, the structure invariably refers to the molecular formulae (e.g., NaCl, MgCl2, etc.). Organic chemists always write a two dimensional view of the molecules while representing the structure of the molecules (e.g., benzene, naphthalene, etc.). Physicists conjure up the three dimensional views of molecular structures while biologists describe the protein structure at four levels. The sequence of amino acids i.e., the positional information in a protein – which is the first amino acid, which is second, and so on – is called the primary structure (Figure 9.3) of a protein. A protein is imagined as a line, the left end represented by the first amino acid and the right end represented by the last amino acid. The first amino acid is also called as N-terminal amino acid. The last amino acid is called the C-terminal amino acid. A protein thread does not exist throughout as an extended rigid rod. The thread is folded in the form of a helix (similar to a revolving staircase). Of course, only some portions of the protein thread are arranged in the form of a helix. In proteins, only right handed helices are observed. Other regions of the protein thread are folded into other forms in what is called the secondary structure. In addition, the long protein chain is also folded upon itself like a hollow woolen ball, giving rise to the tertiary structure (Figure 9.4 a, b). This gives us a 3-dimensional view of a protein. Tertiary structure is absolutely necessary for the many biological activities of proteins.

Figure 9.3 Various levels of Protein Structure

Figure 9.4 Cartoon showing : (a) A secondary structure and (b) A tertiary structure of proteins

9.8 Nature of Bond Linking Monomers in a Polymer

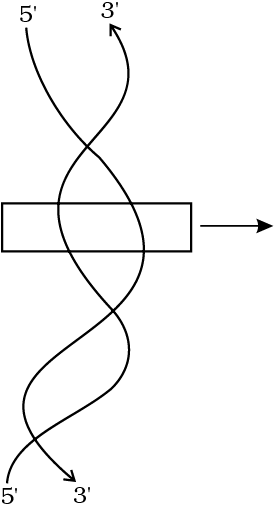

In a polypeptide or a protein, amino acids are linked by a peptide bond which is formed when the carboxyl (-COOH) group of one amino acid reacts with the amino (-NH2) group of the next amino acid with the elimination of a water moiety (the process is called dehydration). In a polysaccharide the individual monosaccharides are linked by a glycosidic bond. This bond is also formed by dehydration. This bond is formed between two carbon atoms of two adjacent monosaccharides. In a nucleic acid a phosphate moiety links the 3’-carbon of one sugar of one nucleotide to the 5’-carbon of the sugar of the succeeding nucleotide. The bond between the phosphate and hydroxyl group of sugar is an ester bond. As there is one such ester bond on either side, it is called phosphodiester bond (Figure 9.5).

Nucleic acids exhibit a wide variety of secondary structures. For example, one of the secondary structures exhibited by DNA is the famous Watson-Crick model. This model says that DNA exists as a double helix. The two strands of polynucleotides are antiparallel i.e., run in the opposite direction. The backbone is formed by the sugar-phosphate-sugar chain. The nitrogen bases are projected more or less perpendicular to this backbone but face inside. A and G of one strand compulsorily base pairs with T and C, respectively, on the other strand. There are two hydrogen bonds between A and T and three hydrogen bonds between G and C. Each strand appears like a helical staircase. Each step of ascent is represented by a pair of bases. At each step of ascent, the strand turns 36°. One full turn of the helical strand would involve ten steps or ten base pairs. Attempt drawing a line diagram. The pitch would be 34Å. The rise per base pair would be 3.4Å. This form of DNA with the above mentioned salient features is called B-DNA. In higher classes, you will be told that there are more than a dozen forms of DNA named after English alphabets with unique structural features.

9.9 Dynamic State of Body Constituents – Concept of Metabolism

What we have learnt till now is that living organisms, be it a simple bacterial cell, a protozoan, a plant or an animal, contain thousands of organic compounds. These compounds or biomolecules are present in certain concentrations (expressed as mols/cell or mols/litre etc.). One of the greatest discoveries ever made was the observation that all these biomolecules have a turn over. This means that they are constantly being changed into some other biomolecules and also made from some other biomolecules. This breaking and making is through chemical reactions constantly occuring in living organisms. Together all these chemical reactions are called metabolism. Each of the metabolic reactions results in the transformation of biomolecules. A few examples for such metabolic transformations are: removal of CO2 from amino acids making an amino acid into an amine, removal of amino group in a nucleotide base; hydrolysis of a glycosidic bond in a disaccharide, etc. We can list tens and thousands of such examples. Majority of these metabolic reactions do not occur in isolation but are always linked to some other reactions. In other words, metabolites are converted into each other in a series of linked reactions called metabolic pathways. These metabolic pathways are similar to the automobile traffic in a city. These pathways are either linear or circular. These pathways criss-cross each other, i.e., there are traffic junctions. Flow of metabolites through metabolic pathway has a definite rate and direction like automobile traffic. This metabolite flow is called the dynamic state of body constituents. What is most important is that this interlinked metabolic traffic is very smooth and without a single reported mishap for healthy conditions. Another feature of these metabolic reactions is that every chemical reaction is a catalysed reaction. There is no uncatalysed metabolic conversion in living systems. Even CO2 dissolving in water, a physical process, is a catalysed reaction in living systems. The catalysts which hasten the rate of a given metabolic conversation are also proteins. These proteins with catalytic power are named enzymes.

9.10 Metabolic Basis for Living

Metabolic pathways can lead to a more complex structure from a simpler structure (for example, acetic acid becomes cholesterol) or lead to a simpler structure from a complex structure (for example, glucose becomes lactic acid in our skeletal muscle). The former cases are called biosynthetic pathways or anabolic pathways. The latter constitute degradation and hence are called catabolic pathways. Anabolic pathways, as expected, consume energy. Assembly of a protein from amino acids requires energy input. On the other hand, catabolic pathways lead to the release of energy. For example, when glucose is degraded to lactic acid in our skeletal muscle, energy is liberated. This metabolic pathway from glucose to lactic acid which occurs in 10 metabolic steps is called glycolysis. Living organisms have learnt to trap this energy liberated during degradation and store it in the form of chemical bonds. As and when needed, this bond energy is utilised for biosynthetic, osmotic and mechanical work that we perform. The most important form of energy currency in living systems is the bond energy in a chemical called adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

How do living organisms derive their energy? What strategies have they evolved? How do they store this energy and in what form? How do they convert this energy into work? You will study and understand all this under a sub-discipline called ‘Bioenergetics’ later in your higher classes.

9.11 The Living State

At this level, you must understand that the tens and thousands of chemical compounds in a living organism, otherwise called metabolites, or biomolecules, are present at concentrations characteristic of each of them. For example, the blood concentration of glucose in a normal healthy individual is 4.2 mmol/L–6.1 mmol/L, while that of hormones would be nanograms/mL. The most important fact of biological systems is that all living organisms exist in a steady-state characterised by concentrations of each of these biomolecules. These biomolecules are in a metabolic flux. Any chemical or physical process moves spontaneously to equilibrium. The steady state is a non-equilibrium state. One should remember from physics that systems at equilibrium cannot perform work. As living organisms work continuously, they cannot afford to reach equilibrium. Hence the living state is a non-equilibrium steady-state to be able to perform work; living process is a constant effort to prevent falling into equilibrium. This is achieved by energy input. Metabolism provides a mechanism for the production of energy. Hence the living state and metabolism are synonymous. Without metabolism there cannot be a living state.

9.12 Enzymes

Almost all enzymes are proteins. There are some nucleic acids that behave like enzymes. These are called ribozymes. One can depict an enzyme by a line diagram. An enzyme like any protein has a primary structure, i.e., amino acid sequence of the protein. An enzyme like any protein has the secondary and the tertiary structure. When you look at a tertiary structure (Figure 9.4 b) you will notice that the backbone of the protein chain folds upon itself, the chain criss-crosses itself and hence, many crevices or pockets are made. One such pocket is the ‘active site’. An active site of an enzyme is a crevice or pocket into which the substrate fits. Thus enzymes, through their active site, catalyse reactions at a high rate. Enzyme catalysts differ from inorganic catalysts in many ways, but one major difference needs mention. Inorganic catalysts work efficiently at high temperatures and high pressures, while enzymes get damaged at high temperatures (say above 40°C). However, enzymes isolated from organisms who normally live under extremely high temperatures (e.g., hot vents and sulphur springs), are stable and retain their catalytic power even at high temperatures (upto 80°-90°C). Thermal stability is thus an important quality of such enzymes isolated from thermophilic organisms.

9.12.1 Chemical Reactions

How do we understand these enzymes? Let us first understand a chemical reaction. Chemical compounds undergo two types of changes. A physical change simply refers to a change in shape without breaking of bonds. This is a physical process. Another physical process is a change in state of matter: when ice melts into water, or when water becomes a vapour. These are also physical processes. However, when bonds are broken and new bonds are formed during transformation, this will be called a chemical reaction. For example:

Ba(OH)2 + H2SO4 → BaSO4 + 2H2O

is an inorganic chemical reaction. Similarly, hydrolysis of starch into glucose is an organic chemical reaction. Rate of a physical or chemical process refers to the amount of product formed per unit time. It can be expressed as:

rate =

Rate can also be called velocity if the direction is specified. Rates of physical and chemical processes are influenced by temperature among other factors. A general rule of thumb is that rate doubles or decreases by half for every 10°C change in either direction. Catalysed reactions proceed at rates vastly higher than that of uncatalysed ones. When enzyme catalysed reactions are observed, the rate would be vastly higher than the same but uncatalysed reaction. For example

CO2 + H2O

carbon dioxide water

H2CO3

carbonic acid

In the absence of any enzyme this reaction is very slow, with about 200 molecules of H2CO3 being formed in an hour. However, by using the enzyme present within the cytoplasm called carbonic anhydrase, the reaction speeds dramatically with about 600,000 molecules being formed every second. The enzyme has accelerated the reaction rate by about 10 million times. The power of enzymes is incredible indeed!

There are thousands of types of enzymes each catalysing a unique chemical or metabolic reaction. A multistep chemical reaction, when each of the steps is catalysed by the same enzyme complex or different enzymes, is called a metabolic pathway. For example,

Glucose → 2 Pyruvic acid

C6H12O6 + O2 → 2C3H4 O3 + 2H2O

is actually a metabolic pathway in which glucose becomes pyruvic acid through ten different enzyme catalysed metabolic reactions. When you study respiration in Chapter 14 you will study these reactions. At this stage you should know that this very metabolic pathway with one or two additional reactions gives rise to a variety of metabolic end products. In our skeletal muscle, under anaerobic conditions, lactic acid is formed. Under normal aerobic conditions, pyruvic acid is formed. In yeast, during fermentation, the same pathway leads to the production of ethanol (alcohol). Hence, in different conditions different products are possible.

9.12.2 How do Enzymes bring about such High Rates of Chemical Conversions?

To understand this we should study enzymes a little more. We have already understood the idea of an ‘active site’. The chemical or metabolic conversion refers to a reaction. The chemical which is converted into a product is called a ‘substrate’. Hence enzymes, i.e. proteins with three dimensional structures including an ‘active site’, convert a substrate (S) into a product (P). Symbolically, this can be depicted as:

S → P

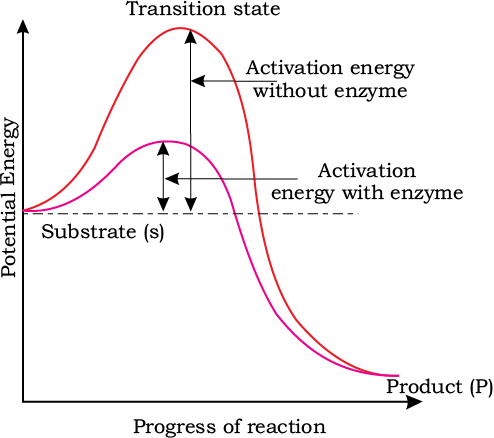

It is now understood that the substrate ‘S’ has to bind the enzyme at its ‘active site’ within a given cleft or pocket. The substrate has to diffuse towards the ‘active site’. There is thus, an obligatory formation of an ‘ES’ complex. E stands for enzyme. This complex formation is a transient phenomenon. During the state where substrate is bound to the enzyme active site, a new structure of the substrate called transition state structure is formed. Very soon, after the expected bond breaking/making is completed, the product is released from the active site. In other words, the structure of substrate gets transformed into the structure of product(s). The pathway of this transformation must go through the so-called transition state structure. There could be many more ‘altered structural states’ between the stable substrate and the product. Implicit in this statement is the fact that all other intermediate structural states are unstable. Stability is something related to energy status of the molecule or the structure. Hence, when we look at this pictorially through a graph it looks like something as in Figure 9.6.

Figure 9.6 Concept of activation energy

The y-axis represents the potential energy content. The x-axis represents the progression of the structural transformation or states through the ‘transition state’. You would notice two things. The energy level difference between S and P. If ‘P’ is at a lower level than ‘S’, the reaction is an exothermic reaction. One need not supply energy (by heating) in order to form the product. However, whether it is an exothermic or spontaneous reaction or an endothermic or energy requiring reaction, the ‘S’ has to go through a much higher energy state or transition state. The difference in average energy content of ‘S’ from that of this transition state is called ‘activation energy’.

Enzymes eventually bring down this energy barrier making the transition of ‘S’ to ‘P’ more easy.

9.12.3 Nature of Enzyme Action

Each enzyme (E) has a substrate (S) binding site in its molecule so that a highly reactive enzyme-substrate complex (ES) is produced. This complex is short-lived and dissociates into its product(s) P and the unchanged enzyme with an intermediate formation of the enzyme-product complex (EP).

The formation of the ES complex is essential for catalysis.

E + S <—> ES → EP → E + P

The catalytic cycle of an enzyme action can be described in the following steps:

1. First, the substrate binds to the active site of the enzyme, fitting into the active site.

2. The binding of the substrate induces the enzyme to alter its shape, fitting more tightly around the substrate.

3. The active site of the enzyme, now in close proximity of the substrate breaks the chemical bonds of the substrate and the new enzyme- product complex is formed.

4. The enzyme releases the products of the reaction and the free enzyme is ready to bind to another molecule of the substrate and run through the catalytic cycle once again.

9.12.4 Factors Affecting Enzyme Activity

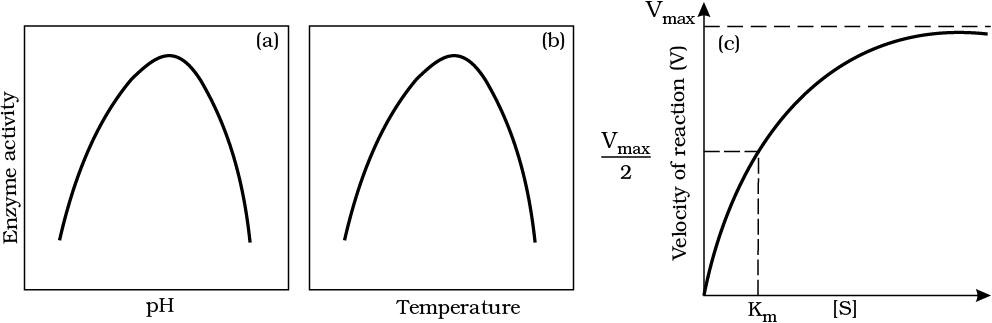

The activity of an enzyme can be affected by a change in the conditions which can alter the tertiary structure of the protein. These include temperature, pH, change in substrate concentration or binding of specific chemicals that regulate its activity.

Figure 9.7 Effect of change in : (a) pH (b) Temperature and (c) Concentration of substrate on enzyme activity

Enzymes generally function in a narrow range of temperature and pH (Figure 9.7). Each enzyme shows its highest activity at a particular temperature and pH called the optimum temperature and optimum pH. Activity declines both below and above the optimum value. Low temperature preserves the enzyme in a temporarily inactive state whereas high temperature destroys enzymatic activity because proteins are denatured by heat.

Concentration of Substrate

With the increase in substrate concentration, the velocity of the enzymatic reaction rises at first. The reaction ultimately reaches a maximum velocity (Vmax) which is not exceeded by any further rise in concentration of the substrate. This is because the enzyme molecules are fewer than the substrate molecules and after saturation of these molecules, there are no free enzyme molecules to bind with the additional substrate molecules (Figure 9.7).

The activity of an enzyme is also sensitive to the presence of specific chemicals that bind to the enzyme. When the binding of the chemical shuts off enzyme activity, the process is called inhibition and the chemical is called an inhibitor.

When the inhibitor closely resembles the substrate in its molecular structure and inhibits the activity of the enzyme, it is known as competitive inhibitor. Due to its close structural similarity with the substrate, the inhibitor competes with the substrate for the substrate-binding site of the enzyme. Consequently, the substrate cannot bind and as a result, the enzyme action declines, e.g., inhibition of succinic dehydrogenase by malonate which closely resembles the substrate succinate in structure. Such competitive inhibitors are often used in the control of bacterial pathogens.

9.12.5 Classification and Nomenclature of Enzymes

Thousands of enzymes have been discovered, isolated and studied. Most of these enzymes have been classified into different groups based on the type of reactions they catalyse. Enzymes are divided into 6 classes each with 4-13 subclasses and named accordingly by a four-digit number.

Oxidoreductases/dehydrogenases: Enzymes which catalyse oxidoreduction between two substrates S and S’

e.g.,

S reduced + S’ oxidised → S oxidised + S’ reduced.

Transferases: Enzymes catalysing a transfer of a group, G (other than hydrogen) between a pair of substrate S and S’ e.g.,

S – G + S’ → S + S’ – G

Hydrolases: Enzymes catalysing hydrolysis of ester, ether, peptide, glycosidic, C-C, C-halide or P-N bonds.

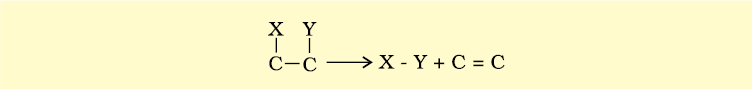

Lyases: Enzymes that catalyse removal of groups from substrates by mechanisms other than hydrolysis leaving double bonds.

Isomerases: Includes all enzymes catalysing inter-conversion of optical, geometric or positional isomers.

Ligases: Enzymes catalysing the linking together of 2 compounds, e.g., enzymes which catalyse joining of C-O, C-S, C-N, P-O etc. bonds.

9.12.6 Co-factors

Enzymes are composed of one or several polypeptide chains. However, there are a number of cases in which non-protein constituents called co-factors are bound to the the enzyme to make the enzyme catalytically active. In these instances, the protein portion of the enzymes is called the apoenzyme. Three kinds of cofactors may be identified: prosthetic groups, co-enzymes and metal ions.

Prosthetic groups are organic compounds and are distinguished from other cofactors in that they are tightly bound to the apoenzyme. For example, in peroxidase and catalase, which catalyze the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, haem is the prosthetic group and it is a part of the active site of the enzyme.

Co-enzymes are also organic compounds but their association with the apoenzyme is only transient, usually occurring during the course of catalysis. Furthermore, co-enzymes serve as co-factors in a number of different enzyme catalyzed reactions. The essential chemical components of many coenzymes are vitamins, e.g., coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NADP contain the vitamin niacin.

A number of enzymes require metal ions for their activity which form coordination bonds with side chains at the active site and at the same time form one or more cordination bonds with the substrate, e.g., zinc is a cofactor for the proteolytic enzyme carboxypeptidase.

Catalytic activity is lost when the co-factor is removed from the enzyme which testifies that they play a crucial role in the catalytic activity of the enzyme.

Summary

Although there is a bewildering diversity of living organisms, their chemical composition and metabolic reactions appear to be remarkably similar. The elemental composition of living tissues and non-living matter appear also to be similar when analysed qualitatively. However, a closer examination reveals that the relative abundance of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen is higher in living systems when compared to inanimate matter. The most abundant chemical in living organisms is water. There are thousands of small molecular weight (<1000 Da) biomolecules. Amino acids, monosaccharide and disaccharide sugars, fatty acids, glycerol, nucleotides, nucleosides and nitrogen bases are some of the organic compounds seen in living organisms. There are 20 types of amino acids and 5 types of nucleotides. Fats and oils are glycerides in which fatty acids are esterified to glycerol. Phospholipids contain, in addition, a phosphorylated nitrogenous compound.

Only three types of macromolecules, i.e., proteins, nucleic acids and polysaccharides are found in living systems. Lipids, because of their association with membranes separate in the macromolecular fraction. Biomacromolecules are polymers. They are made of building blocks which are different. Proteins are heteropolymers made of amino acids. Nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) are composed of nucleotides. Biomacromolecules have a hierarchy of structures – primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary. Nucleic acids serve as genetic material. Polysaccharides are components of cell wall in plants, fungi and also of the exoskeleton of arthropods. They also are storage forms of energy (e.g., starch and glycogen). Proteins serve a variety of cellular functions. Many of them are enzymes, some are antibodies, some are receptors, some are hormones and some others are structural proteins. Collagen is the most abundant protein in animal world and Ribulose bisphosphate Carboxylase-Oxygenase (RuBisCO) is the most abundant protein in the whole of the biosphere.

Enzymes are proteins which catalyse biochemical reactions in the cells. Ribozymes are nucleic acids with catalytic power. Proteinaceous enzymes exhibit substrate specificity, require optimum temperature and pH for maximal activity. They are denatured at high temperatures. Enzymes lower activation energy of reactions and enhance greatly the rate of the reactions. Nucleic acids carry hereditary information and are passed on from parental generation to progeny.